History of the town of Heraklion

To date no Minoan remains have been uncovered within the boundaries of ancient or medieval Heraklion. Nevertheless, the harbour town serving Knossos stood for approximately 2000 years on the site of the modern port and the eastern suburbs of Poros and Katsambas.

Large houses, major workshop facilities and sumptuous rock-cut cave and tholos tombs have been located at the estuary of the River Kairatos, which flows down from Knossos. Excavations have unearthed a significant portion of the town and several dozen tombs. The recent discovery of boathouses in the harbour town by the mouth of the Kairatos at Katsambas is of major significance.

From post-Minoan to Roman times (900 B.C. - 330)

According to historical sources, in post-Minoan times a small town named

Herakleion, which may have served as a harbour for Knossos, stood on the site of the present city. This was located in the area around and to the west of the Archaeological Museum.

The Name "Heraklion"

The Name "Heraklion" was first used during the 1821 revolution. Its existence as a place name had of course been known since antiquity, and was chosen by the revolutionaries to boost national consciousness and link the revolutionary present to the glorious past. Over the following decades the name was used with increasing frequency by Greek intellectuals, merchants and several locals, until it acquired the official sanction of the Ottoman authorities in the Organic Act of 1869.

In parallel with the new name, ordinary folk did of course continue to use earlier names for the town: Megalo Kastro, Kastro and Chora (the last being a generic term used for Greek island capitals).

From the late 6th century onwards the earlier urban centres fell into decline and the population moved into the countryside. The Arabs had control of the trade routes to the East, and external trade began to wane.

From the 7th century onwards the island was subject to repeated pirate raids, led mainly by the Arabs, which brought about the decline of coastal settlements. The inhabitants moved inland to small farming settlements. To deal with this new threat Crete was upgraded to a theme, with Gortyn remaining the administrative, ecclesiastical and economic centre.

In this period there was a settlement identified as Roman Herakleion, which came within the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Knossos. Theodoros, Bishop of Herakleioupolis, is referred to in the Proceedings of the VI Oecumenical Council (786-7) as being third in the hierarchy of the eleven bishops of Crete. By this time

Kastro may well have been in use as a place name for the settlement.

Heraklion was build by the Arab Saracens in 824 A.D.. At the time it was called

Chandax, a name adapted from the Arab word "kandak" that means moat , due to the moat that the Saracens dug all around the city. Iraklion was built on the location where the old harbour of Knossos used to stand. The name survived during the second Byzantine period as

Chandakas, and during the Venetian occupation as Candia. In fact during the Venetian occupation , the whole island was named

Candia after the city.

The Saracens occupation lasted 140 years (824 -961 A.D). During that time Chandax was the safe harbour of the pirates that ravaged and looted the easterm Mediterranean.Immeasurable wealth was concentrated in Chandax, loot from the islands sacked and ships sunk by the pirates.

Nikiforos Fokas

The

Byzantines tried quite a few times to liberate Chandax, with Nikiforos Fokas finally succeeding in 961 A.D. After a long and bloody siege that lasted almost a year. The fort and the walls surrouding the city were totally demolished, and the city burned down. Most of the Saracens were slaughtered, with the rest of them taken prisoners to Konstantinoupolis.

All the valuable possesions of the Saracens were taken also to Konstantinoupolis. According to the historians of the era it took 300 ships to move all that to the capital of Byzantium.Some of these treasures survided through the ages and are on display on the monastery of Megistis Layras at mount Athos.

The sack of Chandax by the Byzantines, marks the beginning of the second Byzantine era which lasted until 1204.

At that time Alexios the 4th heir to the emperor of Byzantium Isaakios the 2nd, who was dethroned by his brother Alexios the 3rd, asked the Pope to help him get back his throne.He was referred to the Crusaders who at the time were starting the Fourth Crusade, and agreed to give Crete to them once they reestablished him to the throne of Byzantium.

Eventually , the Venetians were established in Chandax in 1210. They rebuilted the walls of the fort in order to protect themselves from the rebellions of the locals, the most important being that of the

Kallergis in 1367.

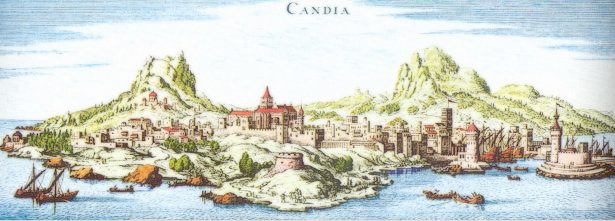

View of Candia from the sea, 1530 - 1540 (Fr. Hogenberg)

Although the Venetians were hated by the locals , and the whole of the island suffered under their yoke, Chandax became probably the most important cultural center in the East Mediterranean during the Renaissance. Many Cretans studied in the island and abroad in Italy, and became famous ( the painter

El Greco ,

Dominicos Theotokopoulos, who was born in Fodele - Iraklion being the best known) .Chandax was a shining light that kept Hellenism alive during these dark times.

After the crashing of the revolution in 1367 the danger from the Cretans had passed. But a new enemy was rising across the sea,

the Turks. So in 1462 the rulers of the city decided to rebuilt and strengthen the walls again. The new wall was designed by one of the most famous military engineers of Venice, Michele Sammicheli. The

construction lasted 100 years. This huge project was funded by extra taxation of the Cretan people, and carried out by the locals who were practically conscripted to work on it. Every Cretan from 14 to 60 years old was forced to work a week every year on the construction.

These walls are tremendous. At some points they are 60 meters thick.

There perimeter is 5.5 km and there are 12 bastions and forts all around. The best known is the Martinengo Bastion, were currently the

grave of the great Greek writer

Nikos Kazantzakis is located.

And yet, for all there size and splendour, these walls fell .

The Turks managed to occupy Chandax in 1669 , after a siege that lasted 22 years!!. But the cost in human life was appaling. After these 22 years 30.000 Christians were dead and 120.000 Turks.

The Turks occupied Crete untill 1897. During that time numerous rebellions by the Cretans were crashed. On

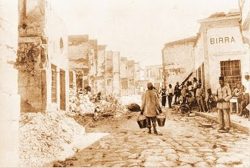

August 25 ,1897 Cretans were slaughtered on the main road to the harbour from the city.

August 25 th Str. today

August 25 th Str. after the events of 1897

|

Eleftherios Venizelos

This road is still named after the event , 25th of August Street. After that, and following negotiations with the Ottomans, Crete was granted autonomy.

During these negotiations, the political star of a great statesman appeared that influenced politics not only for Crete and Greece, but for the whole of Balcans,

Eleftherios Venizelos.

Crete was an independent state from 1897 to 1913. During that time the longing of the Cretans to unite with their brothers in Greece remained. Venizelos became the Prime Minister of Greece in 1909 and continued his efforts to unite Crete with Greece. Eventually , and as a result of the Balkan wars of 1912-13, he succeeded.

From then on the island was an integral part of the Greek state, with its own share in the political and military misadventures of the ensuing years. The Asia Minor disaster in 1922 dealt the final blow to the "Megali Idea", while also marking the beginning of the Greek interwar period (1922-1940). The Greek state then set its sights on internal reorganization and the rehabilitation of over a million refugees.

Thousands of refugees settled on Crete, particularly in Heraklion. At the same time, the last 23 821 Muslim residents were forced to abandon the island. The population grew apace, as new suburbs such as Nea Alikarnassos, Tria Pefka, Katsambas and Patelles were added to the townscape.

Marked changes in the inhabitants' everyday life also occurred. The port was extended, the number of cars on the streets multiplied and the town acquired an aerodrome. Concrete, electricity, the telephone and the radio appeared on the scene in Heraklion, altering time-worn habits and practices. On the eve of World War II, Heraklion was by sight a booming modern urban centre, with bustling mercantile and shipping activity and a lively social scene.

The Italian offensive launched against Greece on 28th October 1940 brought an end to the twenty-year Greek inter-war period, forcing the country to become embroiled in global conflict. Together with Greek victories, the failure of the Italian attack at a time when the Axis powers appeared invincible was hailed with great enthusiasm in democratic countries, yet at the same time provoked German intervention. On 6th April 1941, the German army invaded Greece via the Bulgarian-Greek border, just when the main bulk of the Greek army was fighting on the Albanian front. Despite desperate resistance put up by Greek and British forces, the front collapsed, and by late April almost all Greek territory was under occupation. Crete's hour had come.

Parachute drop during the Battle of Crete, 1940

At 17:30 in the afternoon of 20th May 1941, the sky above Heraklion filled with Junkers Ju52 transport planes, bearing the men of the 1st Parachute Regiment under the command of Colonel Bruno Oswald Bräuer. Codenamed

Orion, this force's mission was to take the city and the aerodrome. The reception accorded by the defenders was "extremely warm", with several aeroplanes being hit before the paratroopers could even jump. Fighting on the ground was intense, as dozens of people from the town and surrounding villages flocked to help in fighting off the invasion. Particularly in the area around the aerodrome, the attackers were pinned down from the very first moment.

The following morning, divisions of paratroopers capitalizing on a renewed aerial bombardment succeeded in getting inside the walls, mainly via the Chania Gate. Street battles broke out in the town, leading to heavy losses on both sides. Finally, in the course of the night, the defenders managed to clear the town and suburbs as far as Tsalikaki and Estavromenos. On the following day Heraklion suffered violent aerial bombardment, aimed at relieving the sorely tried paratroop forces.

Clashes continued over the ensuing days, but the taking of Maleme aerodrome rendered any further defence futile. At daybreak on the 29th of the month, the last British soldiers boarded the warships that had reached Heraklion harbour. At noon on the same day, the town fell to German forces.

Over the course of time, the first resistance groups were set up, aimed at reconnaissance, acts of sabotage and the formation of guerrilla groups. The resistance movement mushroomed day by day. Battles between the occupying forces and guerrillas, sabotage attacks on German installations, executions of collaborators and other high-risk activities became a part of the new reality.

From September 1944 onwards, German and Italian forces began withdrawing from the island's eastern sectors. In Heraklion, the long-awaited day of liberation dawned on 11th October. The atmosphere in the town was highly charged as the last of the Germans withdrew to the jeers of the assembled crowds and the guerrillas, who then entered. Nevertheless, the moment the German rearguard passed through the Chania Gate and further on out, accompanied by Allied officers, the crowds broke out into cheers and songs.

German troops from all corners of the island gathered in the area around the town of Chania. Allied forces and guerrillas avoided attacking them so as not to cause any further damage to the troubled island. There they remained in fortified positions until the final German surrender on 8th May 1945.